By Lisa Brunette

For the past eight years, I’ve worked as a narrative designer in the segment of the digital games industry referred to as “casual gaming.” My audiences have typically been either families (for console games), young women and girls (handheld console games), or women over 40 (downloadable and app games). In this article, I’ll concentrate on the evolution of HOPAs, short for hidden-object puzzle adventure games. This genre was popularized from 2005 to the present by the dominant publisher, Big Fish, which in its PC origins also had a player audience primarily made up of women over 40, with their specific preferences and needs. A lot of work went into getting developers, with their typical “gamer” appetites, to transition away from combat and into intrigue, with story and gameplay focused on solving mysteries and puzzles.

In the wider scheme of game evolution, the HOPA can trace its roots to early text-based adventure games. But today’s typical HOPA player would likely shy away from the fantasy settings that characterize most early examples, such as Dungeon before the advent of personal computers and Zork afterward. In the evolutionary branch I’m analyzing here, supernatural mystery or mainstream adventure in the style of Indiana Jones have been the prevailing genres. But while the adventure served as a sort of frame or ancillary, the hidden-object portion of the HOPA came first.

In a hidden-object puzzle, players search a complex visual scene to spot items on a given list. The first games were little more than digital variations on “I Spy” games the player audience would have already been familiar with, as they were popular mainstays in print newspapers and magazines throughout the U.S.

But even in this nascent incarnation, the impetus to add story was strong. Early developers started out with an idea for scavenger hunt-style gameplay. But they wanted to include a mystery element as well, as a narrative bolstering the game. While these developers were working from what had inspired them and what they wanted to see in a game, data supports this creative move. We know that story acts as a powerful motivator for players to both purchase and play a game. Today we can point to the Entertainment Software Association statistic that an “interesting story or premise” is among the top reasons players buy a game, and this is across the industry— all players, all genres.

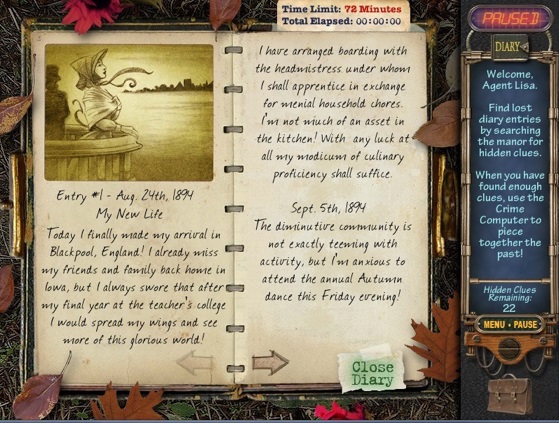

In the HOPAs of 2008, the relationship between text and visuals was one I’d describe as separate, and not entirely equal. It paralleled the relationship between the story and the game play: The story was text-based, and the gameplay was a visual experience, except for a few lines of instruction text. But even in the play, the visuals were mainly static, with few animations. This story-through-text approach was the norm for a few years, with the typical in-game journal serving as the vehicle for story even as more animations became possible. In the below example from Mystery Case Files: Ravenhearst, the story is delivered via the character’s diary, relating her backstory and impressions. Players find the diary entries as they progress through the game, learning more about the character and events.

As the HOPA evolved, the game play took on some of the characteristics of console role-playing games, with movement and exploration within and between scenes now possible. Thus the true adventure portion of the HOPA came to the fore. Players could find an object in the opening scene, store it in their inventory, and use it in a later scene. For example, in a typical HOPA quest chain, players pick up a handkerchief in scene one and realize they can use it to clean a dirty mirror they come across three rooms deeper into the world. However, player discomfort with too much of an open world demanded that the games remain linear. Hence the rise of the “door puzzle,” a mini-game that unlocks a room in a house, as one common use, giving developers a gameplay-based way to control players’ navigation through the world.

The story aspect had evolved as well, toward better overall integration with the gameplay so that it wasn’t relegated to the journal. Players were instead treated to full cinematic cut scenes, not just as intros and outros but within the game, triggered by player action and furthering the story and goal. At this stage, the relationship between text and visuals was one I would describe as complementary, as in the example below. Here the character Death in Riddles of Fate: Wild Hunt speaks directly to the player, who is now fully immersed in the world as a player character.

We also raised the quality bar on the premises and plots, putting more resources into the narrative design team. When Big Fish recruited me to third-party production in 2011, I was the only narrative designer. In just two years’ time, I was managing a staff of four.

At this point, my team was charged with an interesting task: To reduce the amount of text in all our HOPAs. There were many compelling reasons for this charge. First was efficiency; the games were clocking in at anywhere between 50,000 to 120,000 words—about the length of an average novel—for only seven to twelve hours of play. The company’s promise is a “new game every day,” and it took a tremendous amount of time and resources to write, edit, and test basically a novel’s worth of text for each game, plus the costs of translating into multiple languages and then re-editing and testing.

But more importantly for the craft of narrative design, we recognized that ours was primarily a visual medium. While all of us were essentially writers drawn to our work because we loved words, we also knew that visual storytelling held more sway in the context of a game over mere words on the screen. Players had been telling us for years that they did not want to read a lot of on-screen text, or that they ignored the text in the journal. It was a bit of a paradox, as they sometimes said they didn’t care about the story, but this usually meant they were equating story with text. We knew that story could make or break a game, and that the more visual the story, and the more it was integrated with the play, the better the player experience.

Just one example that showcases the results of all this work—and exemplifying the modern HOPA—is ERS Games’ Puppet Show: The Price of Immortality. You can download and play the demo for free here, or you can watch the walkthrough here.

Getting back to that idea of the relationship between text and visuals, the end result is, in the best games in the genre today, a well-woven tapestry of cut scenes and game play. And that old-fashioned journal? We found we could remove it altogether.